“I take to the open road. . . . O public road. . . . O highway. . . . Allons! The road is before us!”

Walt Whitman, The Song of the Open Road, 1882

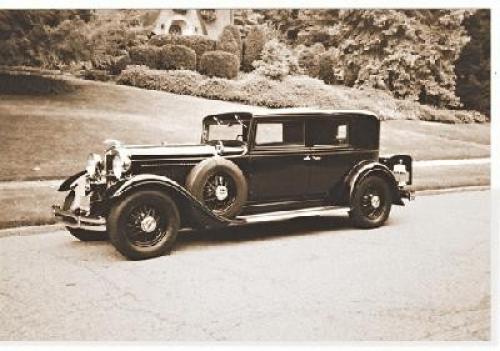

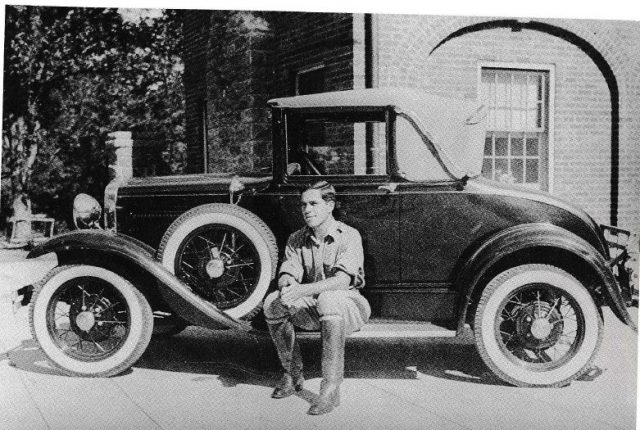

Walt Whitman’s poetic “highway” anticipated Americans’ eagerness for the motorized future, when the Cheek family became enthusiastic patrons of the Age of the Automobile. Their impeccable Cheekwood garage boasted a fleet of fine autos, present-day brands as well as models dispatched to history. The sedan and the wood-paneled (“Woody”) Ford station wagon, the sturdy Buick, the luxurious Packard, the elegant Lincoln town car with wire wheels and whitewall tires, together with the convertible Ford roadster—all filled the inventory of the Cheek family’s vehicles over two generations.

As a country estate completed in 1932, Cheekwood relied on prior decades of automotive modernization and roadway construction. A Good Roads movement had promoted pavement as early as the late 1870s, and a transcontinental highway—the Lincoln Highway—was dedicated in 1913 to inaugurate coast-to-coast travel. (The map that smoothly routed autos from New York City to San Francisco bore little relation to motorists’ realities, for deep ruts, mud, perilous bridges, and unwonted detours deterred all but the hardiest motorists.) By post-WWI, nonetheless, US automobile ownership had reached nearly 6.7 million vehicles, and rubber met the road with tires from Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone, and other Akron, Ohio, manufacturers. The now-legendary U.S. Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles, was inaugurated in 1926, and one year later, the completed U.S. 1 stretched from Maine to Florida.

Wealthy early adopters of the motor car, such as Leslie Cheek, Sr., often opted for chauffeurs, just as their predecessors relied on coachmen to drive harnessed purebred teams. For Mr. Cheek, the onus of steering, manual gear shifting, and synchronizing the brake, clutch, and accelerator pedals (and mastering the fuel-enriching choke) was best left to the chauffeur, who was also charged with maintenance of the vehicles. For convenience, if not necessity, the Cheeks installed a gasoline pump beside the garage. Prior to Leslie Cheek’s death in 1935, the family letters mention his fishing trips to Reelfoot Lake in northwest Tennessee, where he was doubtless driven on two-lane blacktop roadways by Ed Drake, his stalwart chauffeur.

Travels by automobile punctuated the Cheeks’ letters. Mabel proposed a two-week visit to son Leslie, Jr., hoping her daughter might join her. (“I will go in the Buick.”) For his part, Leslie, Jr., had long enjoyed his green Ford convertible roadster, a graduation gift, but his sister, Huldah, perhaps outdid her brother and mother with a 1940 drive to the summit of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington on the former carriage road that now took automobiles up the mountain to the height of 6,288 feet above sea level.

In July 1951, Huldah repeated the drive. “I hadn’t done this since 1940,” she recalled, “and the road is not a bit better than it was then.” Her Ford station wagon engine overheated, but nearby streams provided water for the car’s radiator. (“On the top we walked the dogs, admired the view, and had a late lunch in the Summit House, which is just as unattractive as I remember it.”)

The freedom offered by the automobile inevitably came with chores and costly repairs. With her car just washed, Huldah lamented, “It will get dirty on that [dusty] road whatever the weather.” Worse, in 1943 a repair to the Lincoln cost her mother $100 when its driver, John Reid, seriously damaged one of the doors. “I hope the accident will make him more careful,” Mabel Cheek wrote. “He is the best horseman I ever saw, but not much of a driver.”

Horsemanship flourished in the twentieth century when men and women exercised on the bridle paths, as did Huldah and Leslie, Jr., and some hobbyists relished taking the reins of a horse-drawn coach or light trap. To drive, however, now meant to take the wheel in the new era that one American spelled in four capital letters:

“A-U-T-O.”

Learn more about the incredible machines that moved America and join car enthusiasts from across the southeast on June 18-19, 2022 at the Exposition of Elegance: Classic Cars at Cheekwood. Elegant cars from a bygone era will shine against the backdrop of Cheekwood’s gardens before the weekend culminates with an 11-mile Tour d’Elegance through the streets of the City of Belle Meade.

Blog post provided by Cheekwood’s Writer-in-Residence, Cecelia Tichi, Ph.D.

Cecelia Tichi is an award-winning author and Professor of English and American Studies Emerita at Vanderbilt University. Her books span American literature and culture from colonial days to modern times, but her recent work draws upon the Gilded Age (post-1870) that prompted her book on Jack London and another on seven activists in that tumultuous era.

Cecelia’s research and teaching inspired What Would Mrs. Astor Do? The Essential Guide to the Manners and Mores of the Gilded Age, followed by Gilded Age Cocktails and Jazz Age Cocktails , which set the stage for her mystery crime novels that boast “Gilded” in each title.

Cecelia can be followed on her website: https://cecebooks.com/