Featured Image: Close-up of a marigold in full bloom.

A swallowtail butterfly lands on a marigold.

Hello readers!

My name is Natasha, and I’m the Garden Educator at Cheekwood. My work here involves managing a raised bed vegetable garden (the Cheekwood GROWS Garden) and leading educational programming in this space. In this monthly blog series, I explore cultivated edible plants and our relationships with them in Middle Tennessee.

In Tennessee, marigolds are prolific and easy-to-grow annuals that put on a show all summer long. They are purported to keep pests out of a vegetable garden and are a favorite of butterflies and bees. While certainly not frost tolerant, they will happily bloom well into the fall and reseed for the following year. Just like many culinary herbs, they are edible yet conveniently undesirable to garden foragers such as deer and rabbits. The petals can be used to make herbal tea or tossed in a salad to add some zing.

There are around 50 species of marigold in the Tagetes genus, all of which are native to Central and South America. The showiest is Tagetes erecta, known most aptly by the common name Mexican marigold. I grow these in the raised beds of the Cheekwood GROWS Garden, where without fail they bend and snap under the weight of their own giant blooms and seem to fight against every attempt I make to stake them upright. I don’t mind, though, because their bright orange petals and intense, citrusy aroma are captivating, and it wouldn’t feel like summer without them.

Marigolds are orange because they contain high concentrations of carotenoids, a type of pigment that is also responsible for the vibrant colors of carrots, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, and deciduous leaves in the fall. Carotenoids are ubiquitous and essential in the world of plants; they help them survive high UV levels, attract pollinators, and complete photosynthesis.

The flower’s captivating scent comes from a complex cocktail of chemical compounds called monoterpenes (one of these monoterpenes is limonene, which can also be found in citrus fruits!). Strongly scented monoterpenes allow marigolds to deter predators – this is why gardeners will often plant marigolds among vegetables as a means of pest control.

A marigold about to bloom.

In the case of the Mexican marigold, carotenoids and monoterpenes have an effect unrelated to biological function: Humans have valued and cultivated the brightly colored and scented flowers for hundreds of years. This is not an uncommon phenomenon – all cultivated plants have some sort of aesthetic, medicinal, or nutritional value – but Mexican marigolds have gained cultural importance around the globe, and I think that this is a lovely unintended consequence.

Tagetes erecta were cultivated by the Aztecs as well as the Mesoamerican civilizations that preceded them. In the Nahuatl language, the word for this flower is cempoalxóchitl, meaning “flower of 20 petals”– likely a reference to the plant’s ability to produce an abundance of intricate blooms. The Aztecs selectively bred cempoalxóchitl to develop large flower heads and vibrant colors, and used them extensively in medicine, celebrations, and rituals.

In the 16th century, Spanish colonizers took marigold seeds from the Aztecs back to Spain, and so began the plant’s globalization. They became popular ornamentals in gardens throughout much of Europe and quickly naturalized in North Africa. For this reason, British botanists mistakenly identified marigolds as indigenous to Africa, and the common name “African marigold” has stuck around among English speakers to this day1. Among European Christians, they became symbols of the Virgin Mary, giving us the name marigold (Mary’s gold). Spanish and Portuguese traders brought seeds to the Indian subcontinent, where marigolds quickly became a sacred flower integral to weddings, funerals, and festivals such as Diwali.

Today, cempoalxóchitl flowers play an important role back in their homeland of Mexico during El DÍa de los Muertos, a holiday honoring the lives of the departed and rejoicing in the temporary return of their spirits. The festivities take place at the beginning of November – notably around the same time as Diwali – and marigolds adorn the ofrendas (memorial altars) put together by families to celebrate loved ones. The flowers’ strong scent is believed to guide departed souls from the afterlife to the world of the living. This tradition can be traced back to pre-Hispanic times, when Aztecs used marigolds to honor Mictēcacihuātl, their deity of death, who guided spirits to and from the underworld.

Cheekwood’s 25th El Día de los Muertos festival will take place on November 2 and 3. In preparation for this event, I have been collecting and drying marigold blooms for the past few months and will be facilitating a seed saving activity from 10 AM – 2 PM on both days in the Cheekwood GROWS Garden. I invite you to visit and save some cempoalxóchitl seeds for your garden next year!

Collecting marigold blooms for seed saving.

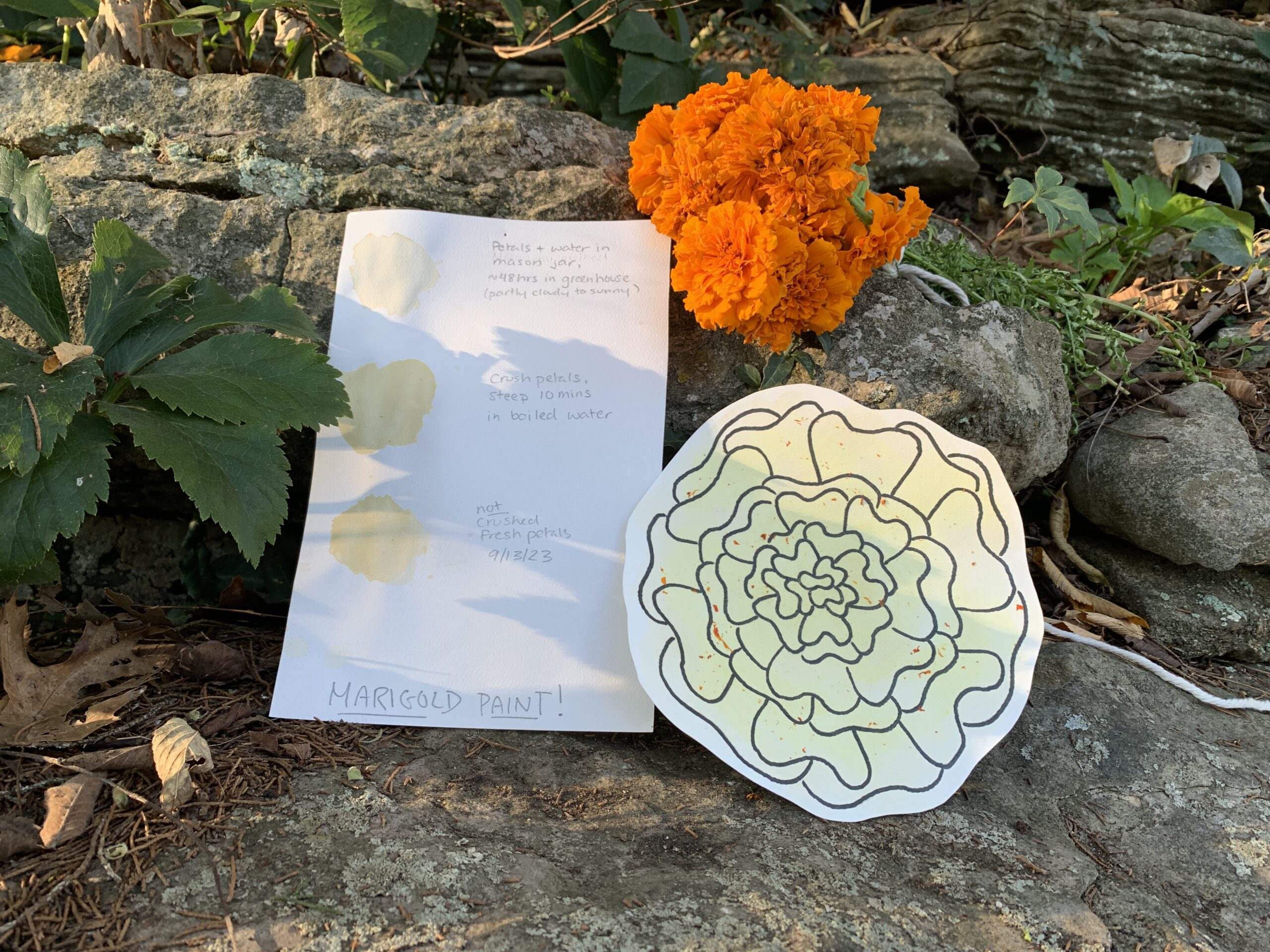

Experimenting with marigold as a natural dye.

Painting with Marigolds

I’m no expert when it comes to natural dyes, but I love to experiment. The vibrant pigments in marigolds make them relatively easy to transfer to paper or fabric! You can do this in a few different ways:

- Crush some fresh petals, either with your hands or using a mortar and pestle. Once the petals have broken down and your hands (or the pestle) have turned orange, you’re ready to paint! Rubbing the crushed petals on watercolor paper will produce a bright yellow pigment flecked with orange.

- Stuff a mason jar to the brim with fresh petals. Boil some water and pour over petals to cover. Let rest for at least 10 minutes (but feel free to wait longer). Strain the petals out of the liquid and use like ink or watercolor. This method produces a less vibrant, but equally lovely, deep yellow shade.

If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future topics, you can contact me at [email protected].

Sources:

- Dalman, Nate. “Marigolds.” University of Minnesota Extension, 2022, link