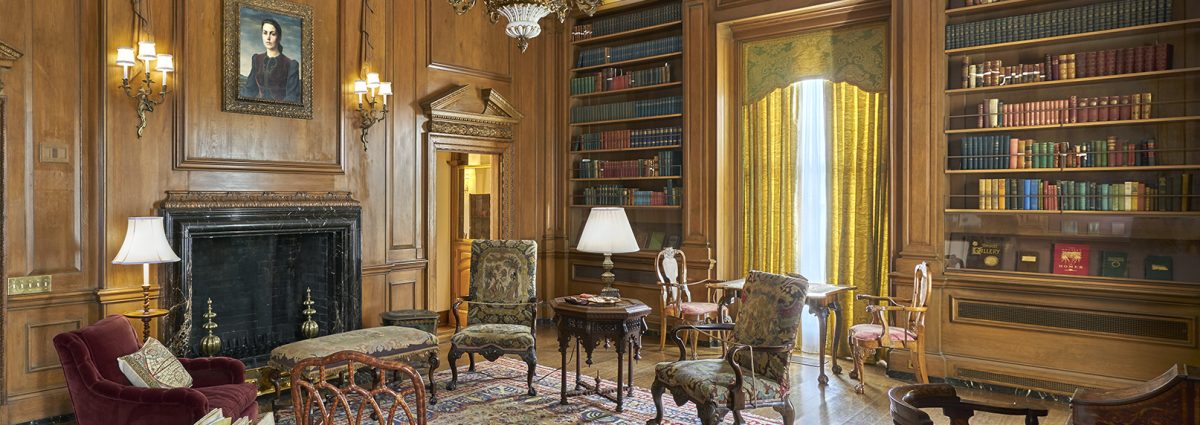

The weather may be frightful, but the fire so delightful, as the song says. So, curl up with a good book in January, as the Cheek family did when their new library was furnished with handsome volumes by enduring marquee authors. The Cheeks’ taste in furnishings harmonized with the advice given by socialite and bestselling author, Edith Wharton, who had co-authored The Decoration of Houses (1914) with the architect, Ogden Codman, Jr.

Edith and Ogden agreed that the private library deserved bookcases that formed “an organic part of the wall-decoration” and that volumes bound in “half morocco or vellum form an expanse of arm, lustrous color.”

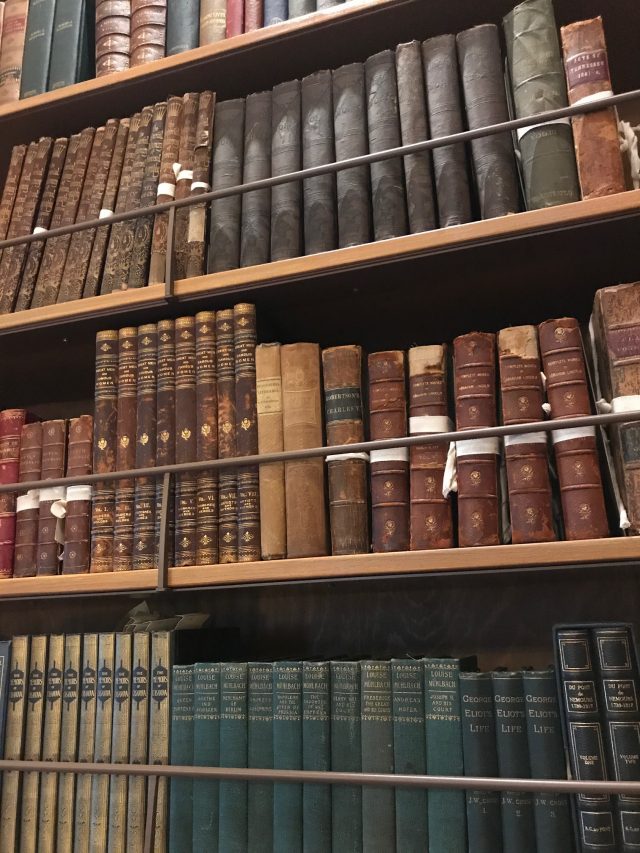

The Cheeks purchased just such lustrous sets—four volumes of The Arabian Nights in gilt morocco, complemented by George Bancroft’s seven-volume History of the United States in calfskin. Thomas Babington Macaulay’s History of England deserved its five-volume purchase in embossed calf, while the Works of George Eliot (a.k.a. Mary Ann Evans) arrived at Cheekwood in ten matched volumes bound in morocco leather.

The authors’ names in their library resound to this day: Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Rudyard Kipling, Lord Byron, Balzac, Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, Victor Hugo, and others. On this side of the Atlantic “Pond,” the library features six volumes of speeches and lectures by New England’s pro-Union statesman, Daniel Webster, while Washington Irving’s Works appeared in ten volumes bound in calfskin. Edgar Allan Poe’s Works comprise four volumes (likewise in calfskin), while Dante’s Divine Comedy arrived in the translation by America’s beloved poet, the multi-lingual Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (also calfskin). The Cheeks, in addition, acquired a recent edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Works in ten volumes (calfskin binding).

Not all authors were available in leather bindings, but the Cheeks purchased some clothbound editions, such as the four-volume Works of Louisa May Alcott, published in Boston. Perhaps Huldah read and reread Little Women.

Photo: Cheekwood Library, Country Life Magazine, 1934, photo credit: Harold Haliday Costain

For January, 2022, one is perhaps tempted to revisit David Copperfield or Washington Irving’s gothic tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” if not Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum” or Hawthorne’s, The Scarlet Letter, a psychological novel of sin and redemption. Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice, a novel of manners and mores, might be this winter’s fare, or perhaps George Eliot’s Middlemarch, entwining politics and romance, egotism and vanity. For episodes of US history that underscore the Republic’s trials and triumphs, one might sample Bancroft’s History of the United States, or look to Macaulay’s History of England.

Then again, if longstanding favorites from Gilded Age and beyond tempt the January reader….

Mark Twain, Roughing It (1872): A romping “Wild West” memoir of the young Twain’s misadventures panning for gold and cub-reporting for the Nevada Territorial Enterprise.

Kate Chopin, The Awakening (1899): A New Orleans matron’s rudest awakening to discover that art and eros do not add up to feminist freedom. (The book was banned, the author ostracized.)

Jack London, The Sea-Wolf (1904): On the high seas, an elite “literary” fellow turns working-class muscleman in league with a toughened genteel lady for mortal combat against the demonic sea captain who harkens to Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost.

Willa Cather, O Pioneers! (1913): A Swedish immigrant girl “reads” Nebraska’s plains to foresee the grasslands becoming America’s breadbasket under her guidance and leadership, making Alexandra Bergson the author’s Alexandra-the Great.

Sinclair Lewis, Main Street (1920): The spirited young wife of a Midwestern doctor tries every which way to bring city sophistication to the stolid community of Gopher Prairie. (Lewis became the first American author to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.)

Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925): Considered an American classic, a novel set during Prohibition in which the self-made American, a bootlegger, may prove the American Dream is a fatal attraction.

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926): The terse Hemingway style offers romance thwarted by WWI wounds in a milieu of sex, drinks, and bullfights, including the famous “running of the bulls” in Pamplona, Spain. Isadora Duncan, My Life (1927): The legendary dancer performed for President Theodore Roosevelt and proclaimed, “Dancing is the Dionysian ecstasy,”Dorothy Parker urged, “Please read this book…. She ran ahead, where there were no paths.”

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937): One reviewer notes the novel explores main character Janie Crawford’s “ripening from a vibrant, but voiceless, teenage girl into a woman with her finger on the trigger of her own destiny.”

Blog provided by Cheekwood’s Writer-in-Residence, Cecelia Tichi, Ph.D.

Cecelia Tichi is an award-winning author and Professor of English and American Studies Emerita at Vanderbilt University. Her books span American literature and culture from colonial days to modern times, but her recent work draws upon the Gilded Age (post-1870) that prompted her book on Jack London and another on seven activists in that tumultuous era.

Cecelia’s research and teaching inspired What Would Mrs. Astor Do? The Essential Guide to the Manners and Mores of the Gilded Age, followed by Gilded Age Cocktails and Jazz Age Cocktails , which set the stage for her mystery crime novels that boast “Gilded” in each title.

Cecelia can be followed on her website: https://cecebooks.com/